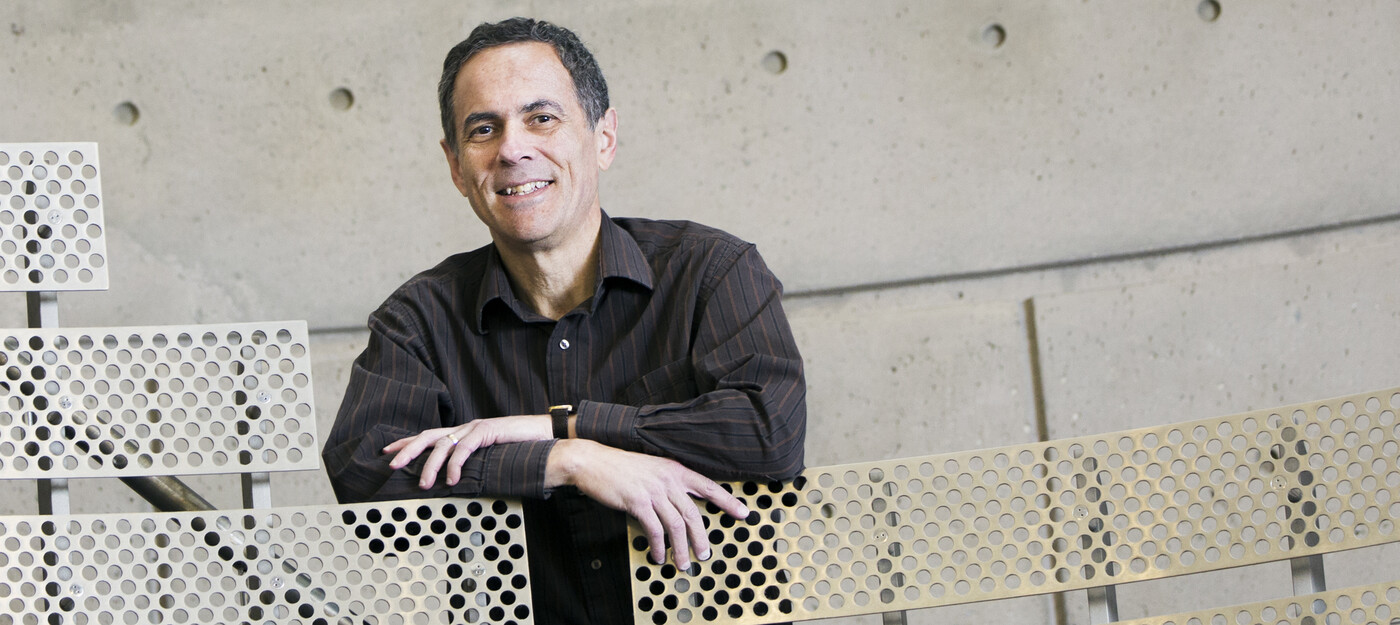

Years of living with undiagnosed Lyme disease left Neil Spector’s heart so badly damaged that he needed a heart transplant. Today, Spector, a Duke cancer researcher, is training for his second half-marathon. In his new book, he shares his story, and encourages people to take charge of their health.

Something Was Wrong But What?

Neil Spector, MD, had just moved to Miami from Boston in the early 1990s when he started experiencing fatigue, muscle pain, weight loss and erratic heart beats. Doctors told him it was stress from the move, but Dr. Spector didn’t buy it. “I knew it was something more; I just didn’t know what,” he said.

Eventually Dr. Spector was diagnosed with life-threatening arrhythmias that were brought under control with an implanted pacemaker/defibrillator. His other symptoms continued until Dr. Spector developed arthritis, and was treated successfully with the same drug used to treat Lyme disease.

“I was incredibly relieved to know it wasn’t all in my head,” Dr. Spector said, still clearly frustrated at his doctors’ unwillingness to make a definitive diagnosis at first. “They didn’t treat me for Lyme disease until every one of the tests they needed came back positive.”

“As I was discovering a new drug for women with breast cancer, I was hoping someone was out there discovering something for me.”

A Heart Transplant in His Future

Nearly 300,000 cases of Lyme disease occur annually, with the most typical symptoms being fever, rash, and a red bull’s eye around the tick bite. In a small percentage of cases, the bacteria that cause the infection comes in contact with the heart, and disrupts the electrical signals that control the heart’s normal rhythm. The resulting, abnormal hearts beats can be fatal.

Dr. Spector took powerful antibiotics through an intravenous line every day for three months to rid his body of the Lyme disease bacteria. “I used to sit next to my patients while I was getting my antibiotics, and they got their chemotherapy,” he recalled. Eventually, the Lyme disease was cured, but his heart was permanently damaged. By the time he moved to North Carolina in 1998, he was told he only had 10 percent heart function and a heart transplant was in his future.

Dr. Spector didn’t let that slow him down. For the next eight years, he worked at a pharmaceutical company where he worked with Duke researchers to help develop a new class of breast cancer drugs, as well as a leukemia drug for children. He coached his young daughter’s soccer team, and travelled extensively. While he knew his health was deteriorating, he kept hoping an alternative to transplant would become available. “As I was discovering a new drug for women with breast cancer, I was hoping someone was out there discovering something for me.”

Transfer Me to Duke

Time ran out when he went to a local hospital to have the battery in his pacemaker changed. The routine visit went down hill fast when his blood pressure dropped dangerously low, and he started having multiple episodes of life-threatening arrhythmias. Doctors tried to replace the pacemaker/defibrillator, but it was enveloped in scar tissue. His heart was no longer strong enough to pump the blood his body needed; his kidneys and liver started to fail.

“The surgeon came in and said, 'you need a heart transplant or you will be dead in 72 hours,’” Dr. Spector said. “I told him, ‘transfer me to Duke.’”

With the odds in his favor –he had AB blood type (the universal recipient) and a common body build – it took only 36 hours before a suitable donor heart became available. A mere 48 hours after transplant surgeon Carmelo Milano, MD, performed the surgery, Dr. Spector was walking three miles around Duke’s cardiology floors.

“It was such a great feeling to have blood flowing through my body again.”

Get a second opinion. A lot of people are reluctant, or are afraid they will upset their doctor. I’ve been to a few doctors who thought they had all the answers. I don’t go to them anymore.

Giving People the Power to Take Control

Today, Dr. Spector, 58, leads the Duke Cancer Institute’s efforts to translate research discoveries into new therapies, and is working to understand how environmental toxins transform healthy tissue into cancers.

He’s spent the past 15+ years documenting his medical journey and the insights he learned. Gone in a Heartbeat: A Physician’s Search for True Healing was published in February 2015.

By sharing his story, Dr. Spector hopes to empower people to take control of their health. “I wouldn’t have written this book if not for pushing people to find a diagnosis, and not being satisfied with their explanation that it was just stress,” he said.

Words of Wisdom

Dr. Spector shares many insights from his experience in his new book. Here are a few:

- Nobody knows your body better than you. You may not know the medical jargon, but you know when somebody tells you something that doesn’t sit well. When that happens, find somebody else to help you out.

- Make the best of every day. It’s okay to feel pathetic once in a while but don’t let your illness define you. Don’t let negative thoughts prevent you from enjoying the beautiful things in your life.

- Take control. You can’t tell a physician, ‘heal me.’ Healing is taking control of your life. It’s saying that your doctor plays a role, but you play an equally important one. Diet, exercise, stress reduction, those are the things you can do for yourself. I think many people forget that.

- Get a second opinion. A lot of people are reluctant, or are afraid they will upset their doctor. I’ve been to a few doctors who thought they had all the answers. I don’t go to them anymore.